Irish settlers in colonial New Jersey made wampum belts, pipes and beads until the late 1800’s. John Jacob Astor traded the wampum for Plains Indian furs.

Much of today’s lower Bergen County, New Jersey was purchased from Hackensack area Native Americans, the Lenni Lenape of the Algonquin, for, as Ralph Kramden might say, “a mere bag of shells.” To the Lenni Lenape, or the “Delaware Indians,” to the nearby Iroquois and Susquehannocks and, later, westward to the “Plains Indians,” including the Comanche, wampum beadwork was no “mere” shell collection.

Many Native American peoples prized the formed, ground and polished product of clam and conch. Wampum was the coin of

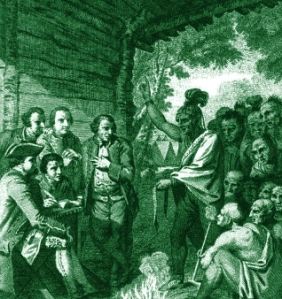

Exchanging Wampum with Native Americans

the realm, a status symbol, the documentation of truth, honor, and understanding, a conduit to God. The exchange of wampum belts and hair pipes was, in certain situations, worth every penny of the signature of the king of any European nation, the finest large cut diamonds, or the work of the most celebrated Old World smiths in gold or silver. At other times, wampum was simple currency, worth x number of pelts, knives or yards of cloth in barter exchange.

The Dutch and Swedish settlers of seventeenth century New Jersey immediately recognized the true value of wampum to the Lenni Lenape. To the northeast, by mid-century, Roger Williams had documented wampum manufacture and protocol among the Narragansett in Rhode Island; towards the end of the 1600’s, to the west, Conrad Weiser and William Penn grew fluent in the language, ceremony and currency of wampum. On the Pennsylvania frontier, traveling with a pocket full of wampum could save one’s life.

Testament to the importance of wampum within Native American society, demand for its production rose steadily from the 1650’s until it peaked in the 1850’s. Recognizing the market opportunity, cottage industries producing wampum sprang up in shore communities on Staten Island and Long Island, New York, and in south Jersey, such as in today’s Cape May and Egg Harbor. Inhabitants of south Jersey shore were quite familiar with the Lenni Lenape, who migrated down the shore each summer, returning inland and north for the remainder of the year.

The most important and productive locale for wampum production was set well back from the Long Island and New Jersey shores, however. Numerous families in the Pascack Valley of today’s Bergen County, New Jersey worked for the most prolific and important of all wampum producers, the Campbell family. For over a century, the Campbell family was the primary producer of high quality wampum given or traded to the Native Americans and, thereafter, between Native American peoples, if a given piece was to circulate as currency, rather than represent a social, political or spiritual bond.

The Campbell Wampum Factory

William Cambell emigrated from Ulster, Ireland in the 1730’s. Family members- at least one of whom married into the locally notable Demarest family- bought and sold properties in Teaneck, New Milford and Montvale, New Jersey. Their property in what is now Park Ridge, however, a purchase of 58 acres formerly the Wortendyke Farm, became the site of the first true factory for the manufacture of wampum in America and, perhaps, the world.

Native American Wampum Beads, Belts and Hair Pipes

The Campbell family wampum factory, or mint, as it was sometimes called, produced wampum in two colors: white and “black.” The black wampum was actually purple- the deeper the shade, the greater the value. Black wampum was worth twice the white. Black wampum was made from quahog clams, and white wampum from conch and periwinkle shells.

The shells were processed into two primary shapes: relatively flat saucers, called “moons”; and tubes, or “pipes.” The conch and periwinkle yielded the white and often pink-tinted moons, while the thick-shelled quahog produced the finest black wampum for the tubes. Holes were drilled in each form so that they could be strung with hemp. The hemp was dyed red to string a concentric stack of moons of graduated size, from the center of which the red tassel would dangle. Moon stacks were worn like pins or badges. The tubes were sold as “hair pipes,” or beads through which the wearer would string his hair; the Comanche, however, became fond of stringing the pipes together in a webbing to form breastplates. Pipes were also strung as necklaces and chokers.

Wampum Moons and Hair Pipes

The wampum factory also produced small round beads, like today’s seed beads. To a lesser extent, the Campbells also manufactured smaller moons, inventoried as “Chief’s Buttons”; large ovular beads, called “Iroquois”; and the occasional pendant shape for earrings. Product derived from other shell types, such as blue mussel and abalone, failed to gain market traction, and were discontinued. Product dyed red and green met similar fates.

Gathering What Other Men Spill- The Industrialization of Wampum Manufacture

The cottage wampum industry on Long Island and in south Jersey never progressed much beyond that, unlike the Campbells operation, which grew by networking Pascack Valley cottage workers to form a supply chain, by exploiting their skills and knowledge as mechanics and blacksmiths, by automating the manufacturing process, and marketing on a large scale as wholesalers to trading merchants in New York City, including John Jacob Astor and the federal government.

Profit margins were high. Raw material cost was nominal. Periodically, Campbell workers, in the early years of the business, would row from the wharf in New Milford down the Hackensack River all the way to Newark Bay, and cross over to Rockaway, Long Island, where they found the clam beds best suited for wampum. The row was roughly 40 miles, but the digs were bountiful. Upon return to New Milford, locals residents were treated to a clam feast: all you can eat, free, just leave the shells. After shucking, the shells were collected and carted by wagon to Park Ridge for processing.

Sometime after 1813, when the famous Washington Market debuted off Fulton Street in New York City, the Campbells bought

The Campbell Wampum Mill

the fish market garbage- empty shells- for next to nothing. They chipped off the “black hearts” on the spot, and loaded a wagon with as much as ten or twelve barrels full of nothing but the choice dark chips. After 1858, they took the new Northern Railroad to Rockland County, offloaded their barrels to a wagon in Nanuet, and drove home to Park Ridge, shortening their horse-drawn journey.

The conch shells, the raw material for the white wampum moons, were also inexpensive. When cargo ships from the West Indies, for example, entered port at New York and emptied their holds, the ship no longer had need for its ballast. Conch shells were commonly used as disposable ballast. The captains amassed their conch shell ballast for next to nothing, if anything at all, and were happy to sell what was otherwise garbage to the Campbells, who were equally happy to recycle the spill at extremely low cost.

The Campbells- who remained farmers themselves- established a network among farmer’s wives and daughters in the Pascak Valley, to whom they sold shells. Workers in this extended, freelance enterprise would chip off the choice portions of the shells, creating wampum “blanks.” The Campbells, in turn, would either repurchase the blanks directly, or from the proprietors along a route of regional country stores that accepted the wampum blanks from the farmers as barter for store merchandise. It wasn’t unusual for twentieth-century Bergen County land developers to discover otherwise inexplicable mounds of clam shells on their inland properties.

Quahog Shell for Black Wampum

The Cambells kept their manufacturing secrets close to the vest; they called the factory a mint for a reason: they literally operated a money machine. As the business grew, they moved its center of operations from their house to what had been a mill for making wool. Still later, they constructed an entirely new mill on the banks of the Pascack Brook, which feeds the Hackensack River. This new mill became a true factory. Following technological improvements, production rose dramatically- tenfold on the high ticket hair pipes. Water power drove grinding and polishing wheels. They had ample space for a team of workers deploying their automated tools, using the fine, clean sand imported at no cost from Rockaway for smooth finishing, and bleaching the white wampum with buttermilk.

The most dramatic improvement in wampum manufacture was an invention by David and James Campbell: a wampum pipe machine. The tool drilled holes in the tubular wampum to create the pipes for hair adornment, necklaces and breastplates. Drilling holes in narrow pieces of brittle shell had forever retarded production and ruined many blanks. The drilling process with spindly hand tools was tedious and tricky. The Campbell’s new machine could bore deep holes in six pipes simultaneously, with far less waste of stock, at a much faster pace. It was the only machine of its kind, although they may have created another for themselves. A single example survives in the local historical society collection. The wampum pipe machine sparked a new and virtually cornered segment of the wampum industry: producing the hair pipes prized by some of the more northern Plains Indians, and the upper Missouri in particular.

John Jacob Astor and Wampum Marketing

The Campbells did not sell their finished pieces directly to the Lenni Lenape, other Algonquin, or the Plains Indians. Ironically, thanks in part to the European settler’s ability to trade wampum for land, there were virtually no Native Americans left in New Jersey during the tenure of the Campbell’s production. Of the few hundreds who remained, some were lured in the mid 1750’s to New Jersey’s only- and the nation’s first- reservation: 3,000 acres alternately known as Brotherton, Edgepillock, Shamong or Indian Mills. Others scattered about the Pine Barrens, working in the local lumber mills or iron forges, or as farmhands; the rest were acculturated to the ways of the European settlers, considered citizens but, on day laborer wages at best, could not afford to buy wampum, even if they retained the desire.

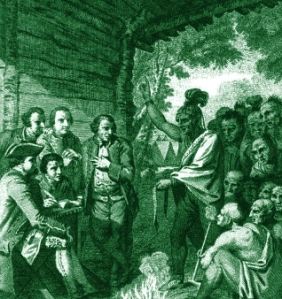

Native American Attire

Rather than retailers, the Campbell were manufacturers and wholesalers, suppling goods to the Native Americans west and north of New Jersey via merchants and agents in New York City, such as for John Jacob Astor. The federal government, through the New York agent for the Superintendent of Indian Trade, a key Campbell customer, found the Campbell wampum especially useful to facilitate land deals as the nation marched west.

Bergen County locals used to boast that John Jacob Astor built his fortune with Pascack Valley wampum. The notion is silly; Astor had plenty of irons in the fire. That said, Astor and the government were likely the Campbell’s best customers. Campbell wampum traveled west, and to Canada, on expeditions to open the fur trade for the American Fur Company. Astor, however, was only one of a number of merchants to whom the Campbells wholesaled. Extant business records indicate that various merchants bought and spread Campbell wampum to the northern and then the southern Plains Indians. Randolph Barnes Marcy brought the Comanche Campbell wampum on his 1852 Red River Expedition. Lewis and Clark’s records reveal that they, too, toted wampum hair pipes as “Sundries for Indian Presents.”

Call to mind William Penn, Conrad Weiser, John Jacob Astor, Lewis and Clark- it’s guaranteed that the word wampum would not be in the first sentence you’d write about any of those men. Then again, one probably wouldn’t imagine that a tiny inland town in northern New Jersey with its glorified trickle of a brook would have become the defacto capital of North American wampum production, either.

He picked her up in PA for a drive to Philadelphia. Their car had engine trouble. They had to drive until very late in the evening. His wife grew tired. She “kept pestering me,” he said in his confession, to “turn the car around and stop somewhere for the night. I suddenly decided to get rid of her because I could not support two homes. She was dozing in the back seat and I shot her in the head, took the body out of the car, and set fire to it.”

He picked her up in PA for a drive to Philadelphia. Their car had engine trouble. They had to drive until very late in the evening. His wife grew tired. She “kept pestering me,” he said in his confession, to “turn the car around and stop somewhere for the night. I suddenly decided to get rid of her because I could not support two homes. She was dozing in the back seat and I shot her in the head, took the body out of the car, and set fire to it.”