From the Diary of Samuel Sewall 27 July 1676:

Sagamore John comes in, brings Mattoonus and his sonne prisoner. Mattoonus shot to death the same day by John’s men.

Sagamore John surrendered in Boston roughly two weeks before John Alderman shot Metacom, the act which effectively ended King Philip’s War, save for a few skirmishes in Maine. Sagamore John’s surrender did not end the atrocities, however.

Sagamore John was a Nipmuc Sachem from Pakachoag in Worcester County. In 1674, he witnessed the deed transferring to Daniel Gookin eight square miles of good Pakachoag land for a mere 12 pounds in New England currency. The down payment for the land consisted of two coats and four yards of cloth. Gookin promised to pay the rest in three months.

Gookin and his friend Reverend John Eliot were instrumental in establishing Pakachoag as one of the towns of Praying Indians. Matoona, a Christian convert, thanks to Gookin, served as a Constable at Pakachoag under the authority of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Matoonas’ son, Nehemiah, ran afoul of Massachusetts’ law in 1671. Nehemiah was accused of murdering an Englishman, Zachary Smith. The traditional narrative, here reproduced from Samuel Gardner Drake’s The Old Indian Chronicle, runs like this:

“Zachary Smith, a young Man, in travelling through Dedham, stopped for a Night at the House of Caleb Church, a Millwright, then residing there. He left, the next Morning, and, when he had been gone about half an Hour, three Indians came along, and went the same Way which Smith had gone. As they passed Church’s House they behaved insolently, throwing Stones and using insulting Language. They were known to the English, having been employed as Laborers among them in Dorchester, and had said they belonged to King Philip. These Indians, on overtaking Smith, killed him for some little Effects which he had about him, and his Body was found “near the Sawmill” in Dedham soon after.”

Matoonas’ son Nehemiah was framed for the murder, and executed. He was  hanged and beheaded. His skull sat on display atop a pole next to the gallows for over five years. Let the record show that the accounts against Nehemiah agreed on neither the sex of the victim nor the town in which the act was perpetrated, let alone the identity of the killer. Matoonas naturally harbored a grudge.

hanged and beheaded. His skull sat on display atop a pole next to the gallows for over five years. Let the record show that the accounts against Nehemiah agreed on neither the sex of the victim nor the town in which the act was perpetrated, let alone the identity of the killer. Matoonas naturally harbored a grudge.

Sagamore John encouraged King Philip. Allied with Nipmuc warriors from Pakachoag and elsewhere, Sagamore John fought for Metacom during Wheeler’s Ambush and the Siege of Brookfield. Matoonas, a leader among the Nipmuc forces, was instrumental during the early raid on Mendon, the initial Massachusetts Bay settlement attacked in the War (the previously attacked settlements were in Plymouth Colony).

Anticipating defeat, Sagamore John ostensibly repented his decision to fight for Metacom. Boston’s Governor and Council offered pardons to those who surrendered. Sagamore John took advantage of the offer, pledged loyalty in exchange for protection, and left Boston unharmed.

On 27 July 1676, Sagamore John returned to Boston with 180 followers and, conspicuously, Matoonas and another of Matoonas’ sons as his captives, bound with ropes.

It took several minutes for Boston authorities to condemn Matoonas to death. Sagamore John “volunteered” to perform the execution. His men allegedly helped. Matoonas was led to Boston Common, tied to a tree, and shot. Boston, still not satisfied, made sure that Matoonas was beheaded. His skull was skewered atop a pole so it could see squarely into the eye sockets of his son’s skull but a few feet away.

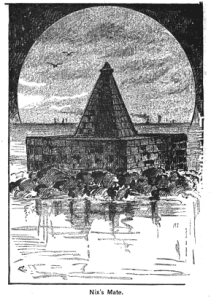

Sagamore John and 19 others who had surrendered later fled town for the woods and back to Pakachoag. The remainder who surrendered did not fare well at the hands of Boston officials. Three were soon executed, accused of torching a house in Framingham; later, eight more were shot in Boston Common. Slave traders bound for the West Indies shackled thirty more. The rest were condemned to life on Deer Island where, without shelter, malnourished, most sickened and slowly died.